What Happens When You Kill The Journalists

Our Palestinian colleagues are being killed. The least we can do is fight back.

Over the last two years, I have felt a growing rift with journalism.

I started noticing the bias early on in my career. When I lived in Palestine, I noticed the way that the foreign press crews always quoted an “IDF Spokesperson”—but always seemed to doubt Palestinian testimonies. Covering Syria showed me just how much the Western media wants young men in the Middle East to be terrorists and how little they care for context. In Iraq, many foreign journalists were happy to write glowing portrayals of the Iraqi units who were backed by the United States to fight ISIS, but turned a blind eye when they committed war crimes.

Since then, I’ve covered many stories of people who have fled these wars to seek asylum in Europe—once again, faced with doubt by both Western governments and the media outlets that serve as their mouth pieces. But since October 7th, 2023, it’s turned into a deafening roar. Suddenly, the journalists who claimed to be unbiased were spreading lies without fact-checking and publishing headlines that shamelessly covered up Israeli war crimes. Journalists who tried to challenge these narratives from inside of their newsrooms faced difficulties and dismissals.

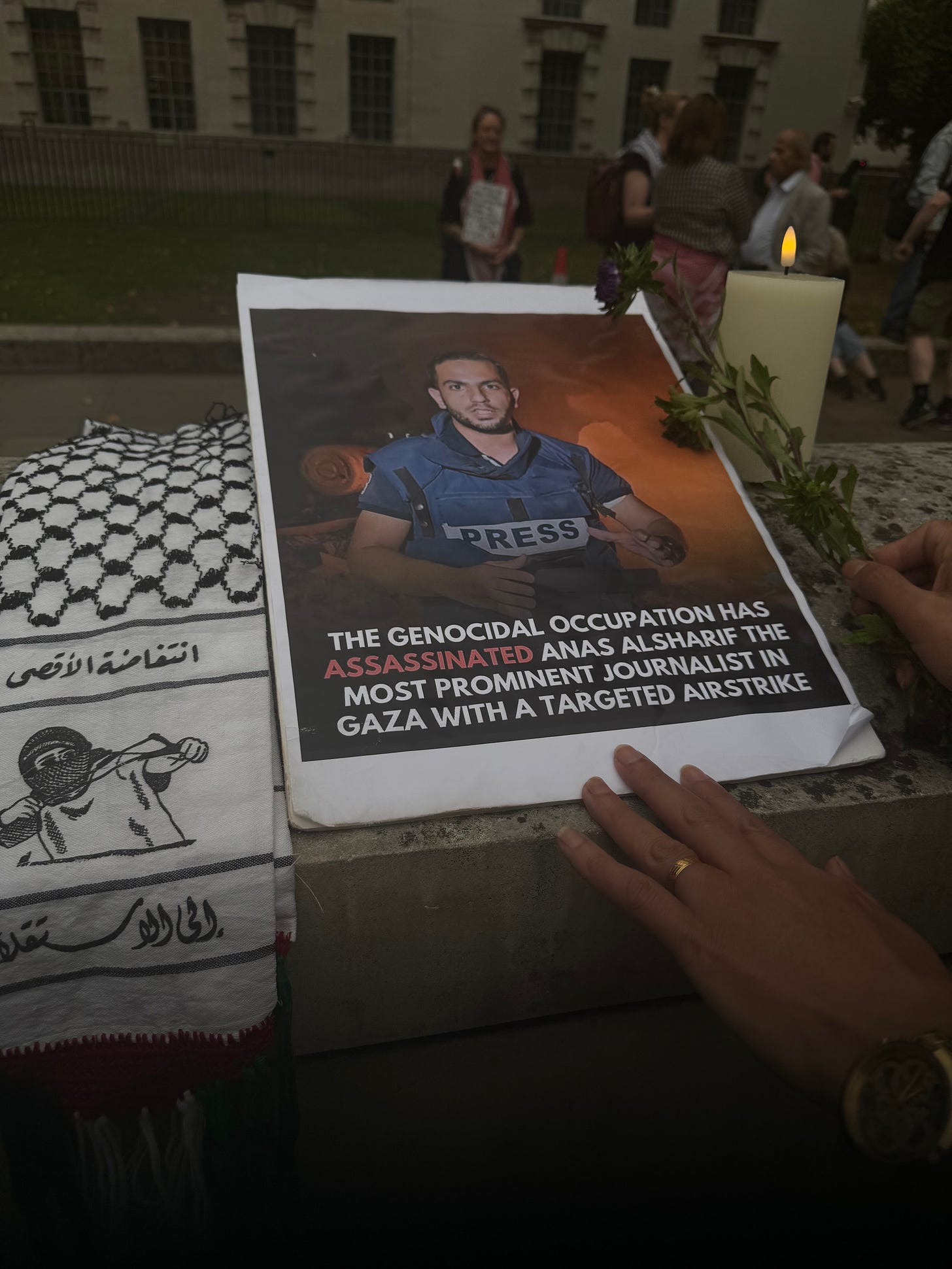

Now, I’m watching as many of my colleagues look the other way in the aftermath of Israel targeting an entire Al Jazeera crew, including their star journalist, 28-year-old TV reporter Anas Al Sharif. This brought the number of journalists killed during this genocide to 192 (this includes Lebanese journalists, killed by Israel as well as Israeli journalists killed during the October 7th attacks, so 184 Palestinian journalists in total). As many reputable press organizations have pointed out, this is more journalists that were killed in World War Two and the Vietnam War, combined.

If you haven’t heard these names before—names like Anas Al Sharif, Mohammad Atallah and dozens of others—it is because these journalists are often working for Western reporters as “fixers” and "translators.” Too often, it means that these local journalists—talented reporters who not only understand the history and context of a place, but have also taken the time and care to build trust among contacts on the ground, and know how to wade through the mire of bureaucracy often required to gain access to a story are uncredited, largely because they are local and therefore “biased.” This is why you see big name TV correspondents (I’m sure you can fill in the blanks) becoming famous for covering these wars even though they’ve never lived in these countries longer than a press stint and probably do not speak a word of Arabic.

But after October 7, 2023, Israel forbid access to the foreign press to cover their “operation” in Gaza. While you have to wonder what they were trying to hide—ahem—this offered a unique opportunity for Palestinian journalists to finally be recognized for their work. Photojournalists like Motaz Aziza, writers like Mosab Abu Toha and of course the personalities like Bisan Oden and Plestia Al Aqad became the eyes of Gaza, writing, photographing and livestreaming the genocide to the world. Al Jazeera—the number one news channel in the Arab World—is the beating heart of this coverage, with legends like Wael Al Dahdouh and Anas Al Sharif tirelessly covering this genocide, through the death of their families, displacement, injury and right up until death.

Now an ordinary and well-adjusted world would recognize these journalists as the bravest people on earth. They’ve received some recognition—Bisan won Emmy Awards for her innovative broadcast journalism and Plestia has published her diaries which are an absolute must-read. But they’ve also been the target of smear campaigns and ridicule, all while surviving a genocide. Bisan’s Emmy nomination was termed “antisemitic” and almost rescinded. Even though Palestinian journalists—like Bisan Odeh, Plestia Al Aqad, Hind Khoudary—have used Instagram to produce their journalism in a way that could have earned the platform a comparison to Facebook and the way that it propelled the Arab uprisings forwards, the tech overlords have cracked down on their content as “hate speech,” shadow-banning, and, in some cases, full on suspending their accounts, drawing dangerous comparisons between testimonies about Palestine and terrorism.

Did I mention that many of these journalists are reporting in English? This is how much they care about their message reaching the world, because the fact of the matter is, most Arabic-speaking audiences do not need to be convinced that a genocide is happening. English-speaking audiences, the ones who are connected to the governments empowering both the Israeli government and the institutions, whether the weapons manufacturers or the Western media narratives that uphold it, do.

This doesn’t just require linguistic fluency—it requires an ability to translate pain and suffering and love for one’s land (ideas that, even for the most verbose among us are often difficult to put into words) into a language that is not your own. It’s given rise to a whole new term in translation called “Palestranslation,” which, as British journalist Sophia Smith Galer describes in a recent video, is inspired by the sorrowfully late Palestinian poet Refaat Al-Areer’s call to Palestinian writers to express themselves in other languages to “combat the multi-million dollar campaigns of Israeli misinformation.”

You also might not have heard of these journalists in the past because they are absurdly young. Anas was twenty-six years old when he started covering the genocide in Gaza, twenty-eight years old when he was killed. It makes me remember what it was like when I was a young reporter, just starting to cut my teeth on the stories that felt important to me, meeting the other, older, more seasoned reporters. I wanted so badly to be like them—someone who put aside all of the conventions of ordinary life to show the comfortable world the realities of war.

Now, I’m shocked at the way that so many of these outlets have turned their backs on their colleagues. A BBC reporter asked Al Jazeera how they managed to have a reporter on the ground in Gaza (refusing to entertain how they, too, could have hired any number of these talented journalists. The New York Times published an article questioning Al Jazeera as a broadcaster and news source. BILD, the most circulated newspaper in Germany and possibly Europe, has just repeated the Israeli government’s accusation that Anas al-Sharif was a terrorist, affiliated with Hamas.

Plenty of journalists have expressed their sorrow privately, but are afraid to speak out publicly out of fear of repercussions. This makes me deeply sad for my profession, where our professional reputation has somehow become diametrically opposed to standing in solidarity with our colleagues. We know better than anyone how everything that ever seemed like it mattered melts away the minute that the lives of our colleagues are on the line. Even if we’re in a friendly competition with them during the day, this melts into camaraderie the minute our work is over.

I can only imagine how much more intense this is for our Palestinian colleagues, who are not only covering devastating violence, but living through it as it affects their families and loved ones. But despite it all, they’ve continued to show up, every day, even when that means shaking from hunger and knowing that an Israeli airstrike could kill them at any minute. Instead of supporting them, most of the Western world is doubting their testimonies, censoring ourselves, in favor of living a comfortable life.

But it’s our Palestinian colleagues, people like Anas and too many others that show us what journalism is, why it’s important and why we must do everything in our power to protect it. The least we can do is fight back.

The control & hold on American journalists is so deeply rooted in fear. I remember during the Black Lives Matter protests, I had a colleague at CNN, who shared with me that they were not allowed to publicly post anything that showed support for their black colleagues for their black friends. And so they were even several white journalists, who are so afraid to lose their jobs so afraid to stand up to bosses that they went along with it. And it’s frightening to me our news organizations have become a place which simply reflects what we see in society: fear based obedience rather than what journalism was supposed to be — which is a revolutionary Call, holding powers and authorities accountable